It was a Friday the 13th that no one will ever forget. On March 13, 2020, school administrators from Kern County’s 47 districts gathered to make an agonizing decision: should schools remain open or close in response to the growing threat of COVID-19? At the time, there were no confirmed cases in the county, and schools were considered essential — providing not just education, but meals, childcare, and stability for thousands of families. The hope was to keep classrooms open as long as possible.

That hope quickly faded.

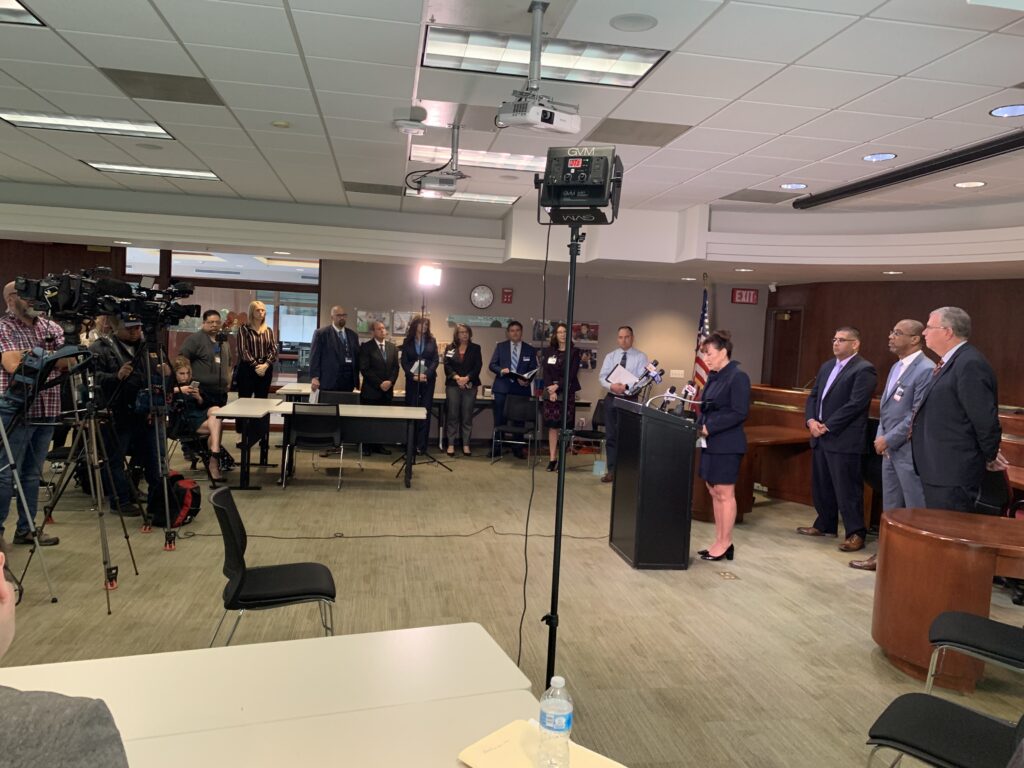

By March 16, after urgent consultations with public health officials over the weekend, then Kern County Superintendent of Schools Mary C. Barlow and then Kern County Public Health Director Matthew Constantine made the difficult decision to recommend that all schools temporarily be shuttered no later than March 18.

Kern County education leaders and Kern County Public Health held a news conference on March 16, 2020 where it was announced that schools would temporarily be shuttered.

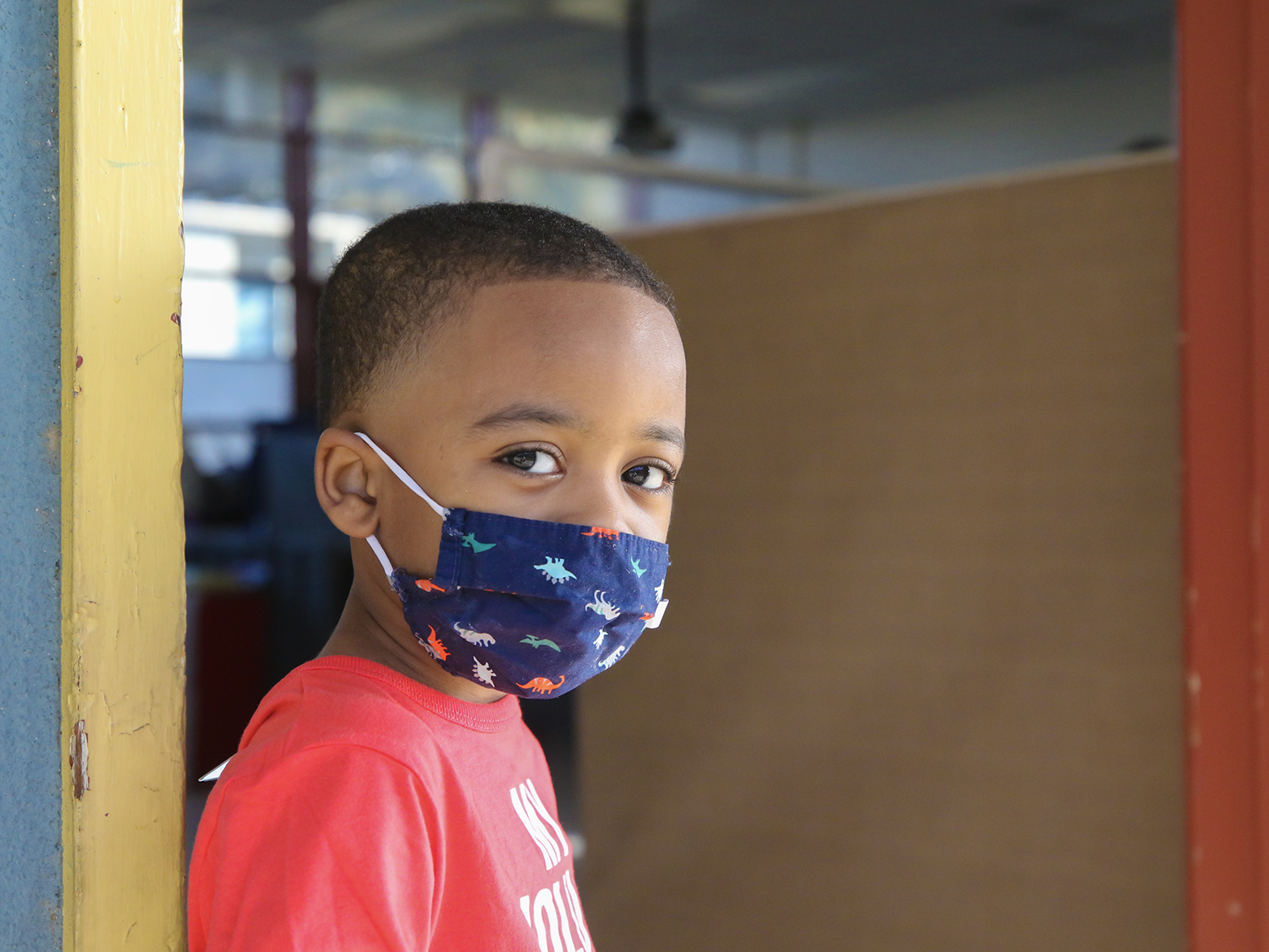

KCSOS facilitated the delivery of PPE to schools all over Kern County in the early days of the pandemic.

Initially, many believed the closure would last only a few weeks. Instead, it stretched through the rest of that school year and well into the next, fundamentally reshaping the educational landscape in Kern County. The sudden shutdown sent shockwaves through the community. Teachers, untrained in virtual instruction, scrambled to redesign their lessons. Parents, already navigating the uncertainty about the changing world around them, found themselves taking on the role of educator. Students, cut off from their routines and peer interactions, struggled to adjust.

“We had to pivot overnight,” recalled Dr. John Mendiburu, Kern County’s current superintendent of schools. “It wasn’t just about learning — it was about making sure students had access to technology, internet connectivity, and basic necessities like meals that so many in our community rely on.”

While their physical buildings were closed, schools continued to serve as lifelines for the community.

“Grab and Go meal programs ensured that students who depended on school meals were still fed. By April 2020, meal distribution expanded to include extra food for weekends, with thousands of meals being distributed daily,” Mendiburu recalled.

The transition to remote learning exposed deep disparities. Thousands of Kern County students — particularly those in rural and underserved communities — lacked reliable internet access or even a device to connect to online instruction. Districts initially relied on paper learning packets while assessing the scale of the technology gap.

The numbers were staggering: 40,000 students had no access to a computer or reliable internet at home. In response, KCSOS led a countywide effort to bridge the digital divide. More than 20,000 Chromebooks and 5,700 Wi-Fi hotspots were sourced, purchased, and distributed. But securing enough devices was a challenge. Demand was overwhelming nationwide, forcing educators to find creative solutions. School buses were repurposed, for a time, as mobile Wi-Fi stations, school parking lots became internet access hubs, and partnerships with companies like Bank of America and Valley Strong Credit Union helped fund additional technology.

More than 20,000 Chromebooks and 5,700 Wi-Fi hotspots were sourced, purchased, and distributed to school districts to aid in distant learning in the early days of the pandemic.

To further support students, KCSOS launched a partnership with Canvas, providing a structured online learning platform free to any Kern County district that needed it.

“We did not have the luxury of time,” said Lisa Gilbert, Deputy Superintendent of Instructional Support at KCSOS. “Our team worked around the clock to create a turn-key solution for teachers.”

It’s a system that many school districts continue to use post pandemic.

Despite extraordinary efforts, many students struggled to engage. Chronic absenteeism spiked, and academic gaps — particularly in math — grew wider.

But the challenges went well beyond academics. Isolation, uncertainty, and loss took a heavy toll on students’ mental health. Schools saw an increase in anxiety, depression, and behavioral issues, with many students struggling to reintegrate when in-person learning resumed.

“Schools have gone to great lengths to expand their counseling services, strengthened trauma-informed practices, and have opened wellness centers that cater to unique needs of students and families,” Mendiburu said.

While the impact of the pandemic persists, gains have been made thanks to targeted interventions in recent years. Extending learning opportunities outside the traditional school day and investing in academic interventionists to work closely with struggling students have helped move the needle. Schools have also increased the use of diagnostic assessments to tailor instruction and monitor progress through the implementation of the Kern Integrated Data System (KiDS).

“KiDS ensures schools have access real-time data to make the most informed decisions on student outcomes,” Mendiburu said.

Perhaps the most significant shift has been in how education is delivered today. Hybrid learning models, digital tools, and independent study options are now permanent fixtures, offering students greater flexibility. And schools have become more than just academic institutions — they are now comprehensive support centers, providing wraparound services such as mental health care, after-school programs, and family assistance through the Community School initiatives.

“Education will never be the same as it was before 2020,” Mendiburu reflected. “But in many ways, we’ve become stronger, more resilient, and better prepared to meet the needs of our students — no matter what challenges come next.”

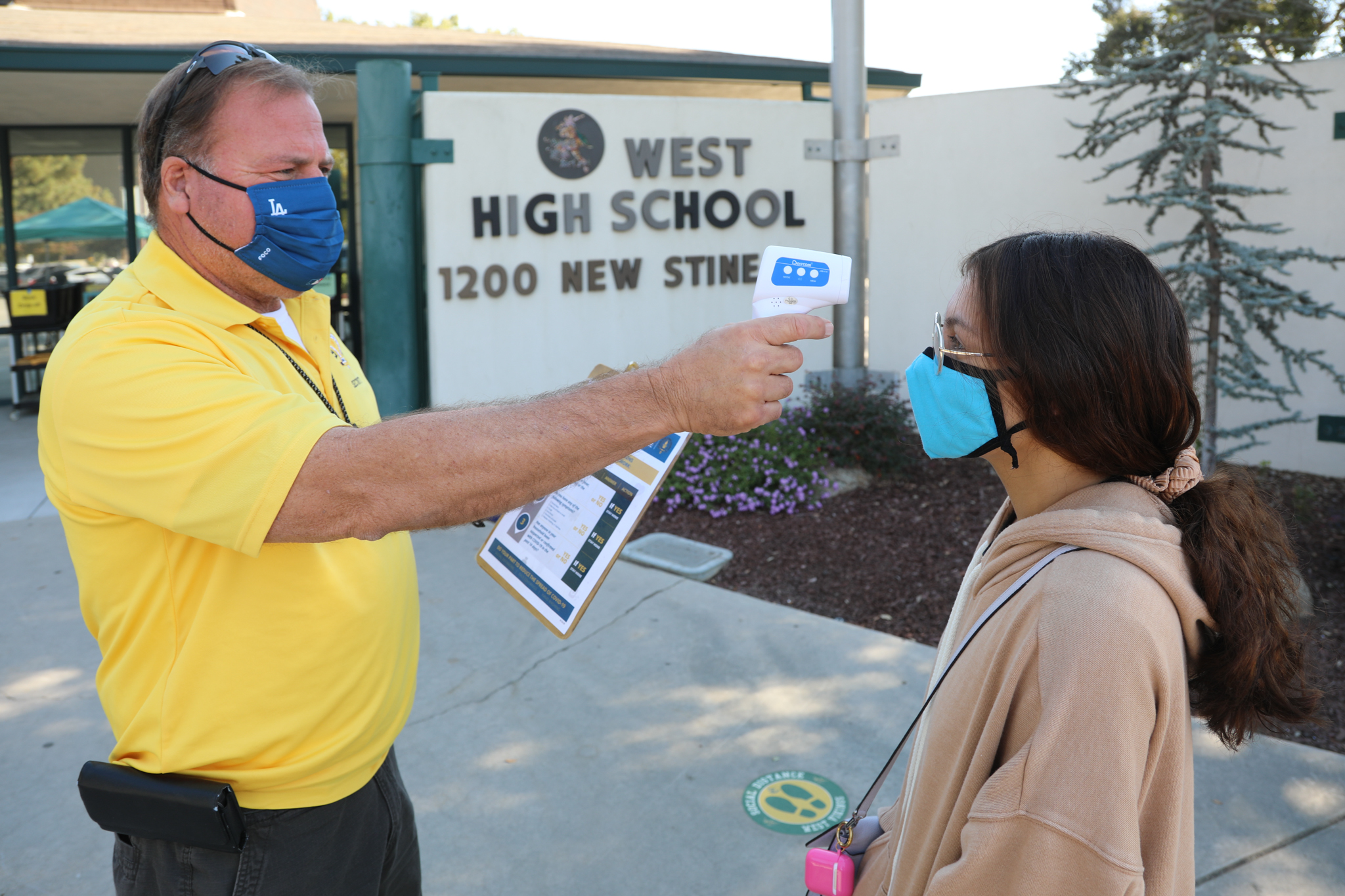

Health screenings became a routine part of the school day when schools re-opened for in-person instruction in 2021.

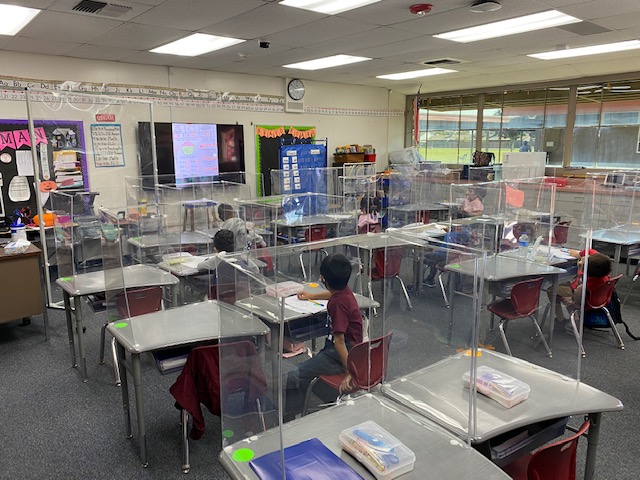

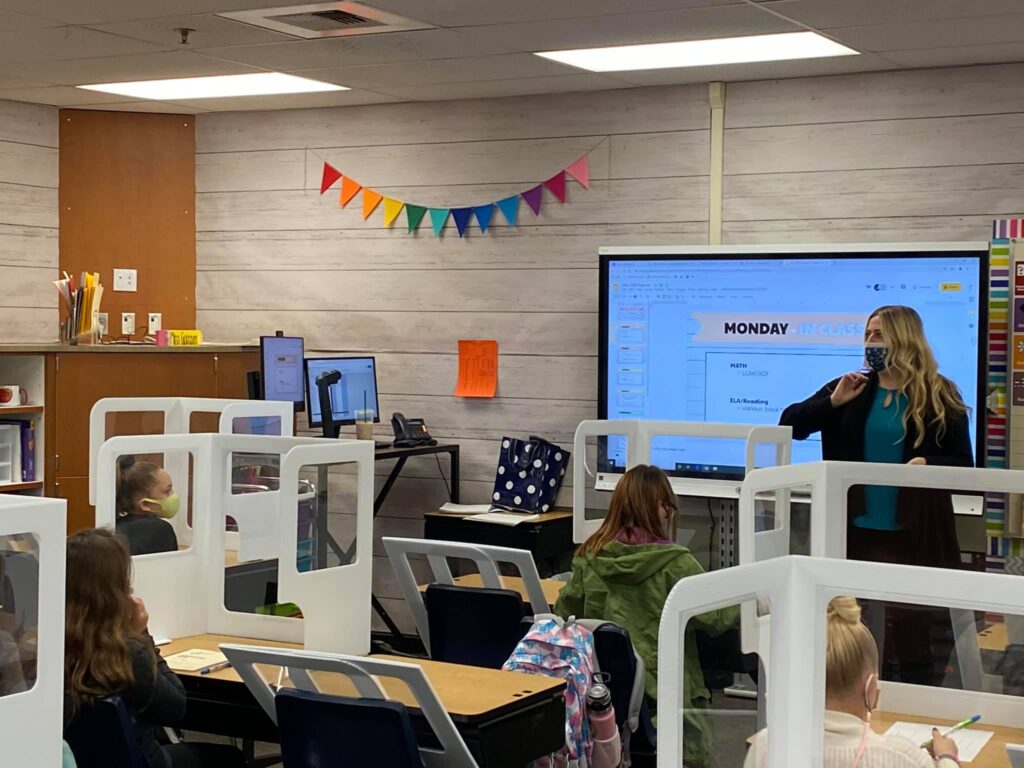

When schools resumed in-person instruction, classrooms looked different. Desk barriers and other social distancing strategies were used to limit the spread the virus. COVID-19 response funds allowed schools to improve their facilities to address the rapid spread of airborne viruses, including HEPA filtration and upgraded air conditioning in buildings that previously lacked it or were in disrepair.

By Robert Meszaros

Rob Meszaros is Director of Communications for the Kern County Superintendent of Schools, where he has served since 2012. In his role, Meszaros oversees media relations, internal and external communication strategies, publications, Marcom, branding, and multi-media content creation. Before joining KCSOS, Meszaros was the PIO for CSU Bakersfield and earlier worked for seven years at The Bakersfield Californian.